But I Don't Play Games

The shifting demographics of gaming and donating are something NGOs shouldn't ignore.

“But I don’t play games”.

That’s the most common objection we got, when we were putting together a group of players for our most recent tournament.

That’s what Apptessence does: we built a system for organising tournaments: we even built a game to play in the tournaments. When people play in our tournaments, they fund NGOs. And we think this is the future.

Not everyone said they didn’t play, of course: as I said in my first post to Substack, we tend to think of age as a demographic divider when it comes to games. But that wasn’t always the case, talking to the potential players.

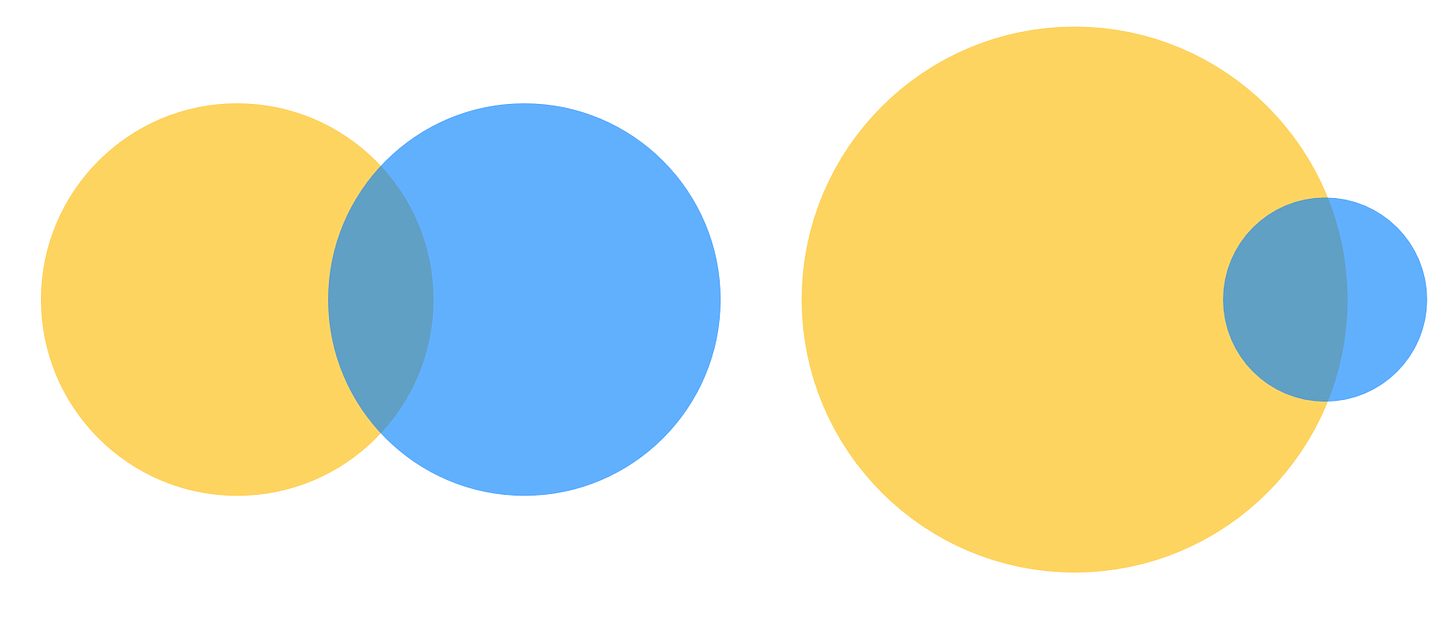

When we talked to iDE recently, we included in the presentation a slide that had two figures in it:

On the left, the two circles represent the size and overlap of gamers and donors in the US today. Gamers are defined as anyone who plays at least one game on any platform each week. And donors are anyone who contributes a sum over (iirc) $500 to an charity or NGO each year. Last we checked, those were two groups of around 250m each.

It’s hard to pin down, but the general indicators are that the overlap is about as minimal as it could be.

The venn diagram on the right shows where the trends are taking us: the people who make up the group that donates (the blue circle) will shrink dramatically; and the people who play games will grow.

How much time lies between the two diagrams? Maybe ten years, maybe less. To a great extent, the donors are dominated by the Baby Boomers, and that generation is for the most part the oldest generation remaining in any great numbers. They’re leaving us.

It Might Not Look Good For NGOs, But…

Gamers will grow because that’s what we see happening now: there is a generational inflection point, which is the point somewhere back in the 90’s, and maybe earlier, when it was normal to have a console in the house; as common as a VHS machine or a television had become in other eras.

In both those cases, the new technology brought radical changes between the generations that experienced them as new, and those who grew up with them around. And that sets a cultural/recreational baseline that establishes life-long consumption of those media. People who depended on arcades for games mostly didn’t carry that interest into older age; those who had a Nintendo or Atari at home during elementary school are far more likely to play games when older.

The upshot: if an NGO depends on older, more established donors, that group will increasingly include gamers as time goes by.

Going a Bit Deeper

But there’s another point here. Will the number of people donating who play games only be represented by that ¾ moon of blue that peeks into the big yellow circle? We don’t think so.

So there’s another, slightly more detailed way to see this situation. If we say that the blue circle represents those who are above some age-limit, and also donate to charities, we can define a group among the gamers who are below that limit, but donate. So the blue circle shrinks a bit, and we put them in the pink circle below.

Looking ten years ahead, what we’re building our business on, is the expectation that the pink group will grow.

But not just that: as I’ve tried to communicate in second diagram, age will probably stop being an objection, as I encountered it among our prospective players. The pink group of player-donors will grow, but it will also cross that age demarcation. So we’ll have a complex situation: who plays? Who gives? Who does both? What age? Who does neither?

In five years, we’re betting that someone who says to you, “I don’t play games”, will sound a lot like someone who says to you today, “I don’t have a mobile phone”. Today, there’s a sense of exclusion that goes with eschewing phones, or at least most of us think there is.*

Similarly, the idea of not engaging in games as part of ordinary life will seem to be a kind of missing out. So, we’re building a service that starts with the premise that the number of people who do play games is going up, the age they play them until is going up, the pervasiveness of the platforms they play them on is going up, and what needs to be explained today– playing this will let you do that – will seem easy to understand, even obvious.

Here’s the upshot: People won’t just play games as a form of leisure, but because they facilitate actions that they want to engage in, like donating.

A Fundamental Change?

And there’s more to it that NGOs need to think about – especially those whose fundraising model is based on broad-based subscription. That subscription model has changed over the years; mass mailings, websites, telephone solicitation, TV advertising, robocalling, call centres, email campaigns, social media – the NGO sector has been very prepared to embrace new models for popular fundraising throughout the years.

The advent of games, and maybe our fundraising model may mark a watershed in this approach. All previous fundraising models I’ve mentioned have had as their goal the wrestling of a slice of the attention of a potential donor, out of their day-to-day activities. They were different, but they shared the goal of getting you to stop doing what you were doing, pay attention to the message, and take action.

Audiences Everywhere

And, as I also talked about briefly in the first Substack post, this is the Age of Audiences. Audiences – or at least contact databases – are the hard part of what the current model has depended on, in the NGO fundraising world.

Our premise is that grabbing attention from people in that way is unnecessary if what those people want to do, prefer to do, becomes the basis of the donation process. I’m going to play games anyway, and I’m going to stream anyway, and I’m going to watch streamers anyway. That’s what happens in the big yellow circle.

This isn’t far from the logic of getting donors onto monthly donation automatic schedules. The hard part is getting attention: converting that to a monthly donation is a lot more efficient than a one-time donation. We reverse this: the attention has been already gotten, in each and every stream: let’s work with that community to put it to a use that benefits everyone involved to a greater degree.

Mailing lists, Nielsen ratings, phone lists, SEO, influencers have all been necessary as part of what NGOs who depend on direct public donations do. Each of these has a market value, and that means that those NGOs become less efficient, because they pay for that access, by bidding against others who may have deeper pockets and more motivation. And from there, we get the backlash, based on the perception that NGOs waste a lot of money to deliver anything to those who supposedly benefit.

By contrast, the platforms that streamers depend on, like Twitch and YouTube and Facebook control and fundamentally undervalue the attention of streamer audiences.

So, we’re trying to do something that finds the synergies. Provide a simple activity that anyone can engage in, in a gaming context. Make it a game that has low barriers to entry for someone who doesn’t play games. Only demand a tiny slice of time – 3 minutes – and create an open ended play window for that participation, so busy folks can squeeze it in.

But most of all, aim it squarely at the audiences that exist, among game streamers, and the many other real-time, or near-real-time media creators. Let them benefit. Give those audiences something new to broaden their engagement with the streamer; and ensure that win or lose, there’s a great feeling knowing that as a group of gamers – or just, you know, people – you made the world a little bit better.

* A Closing Note

Awareness of the gamification of work and society took a sharp uptick when Facebook renamed itself Meta, and announced a commitment to their metaverse project. Your chances of hearing about metaverse ideas went way up then; basically, the technologies built for gaming are being used to build work environments in that iteration of the metaverse.

But if you were a family in a failing business thanks to the pandemic, in an emerging economy like the Philippines, you probably were way ahead of that. For you, Axie Infinity was probably something that you’d already taken a look at, maybe even shifted to as a source of income.

Axie has turned out to be the metaverse for the powerless. It’s an all-gamified environment that stands in for work, replaces work: and millions of people have turned to it. Families, businesses were saved by it.

Then, about a year ago, Axie, which runs within a virtual currency space, had a massive crash, and thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of people were financially ruined, completely.

We’re in Cambodia, just across the border from Vietnam, where Axie was developed. And these malignant models of gamified commerce and employment are, cruelly, meant to work best in economies like this one, where people have less and make harder choices.

That reality is why we built Apptessence and WordsBy2 in ways that are consistent with what we think have to be the ethical basis of a gamified economy. And more personally, we built this system to help this kind society of good people, who helped me during the pandemic, giving me a safe place to live.

And these are things we want to talk about, in one or more of our future Substack posts.

Thanks for reading.

Dan, Founder, Apptessence.